Headquarters (principia) at the fort of the Tenth Legion in Nijmegen

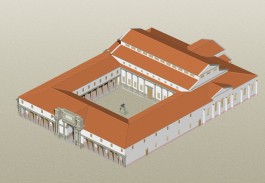

The reconstruction Kees Peterse created of this headquarters shows a building of surprising size and grandeur. The exquisite computer-generated images bring the atmosphere of the rooms to life and depict details like the imposing entrance gate, the inner courtyard, and the great hall or basilica with the regimental shrine.

As in every Roman fortress, the headquarters (principia) was situated at the centre of the legionary fortress in Nijmegen. That was a building with four wings around a large, rectangular courtyard. One wing of the principia bordered the main street through the fortress, the via principalis. The portal providing access to the principia was located on this side. The wing on the opposite side of the courtyard was deeper than the other three and consisted of a great hall (basilica) with a series of rooms behind it. On the longitudinal axis of the principia, directly opposite the portal was a sacred space, the aedes. Here, the legion’s standards and emblems were kept, along with the Aquila, the golden eagle, the most prominent standard. One or more rooms next to or below it usually served as a treasury (aerarium) where the pay chest was kept. Assemblies could be held either in the courtyard or the hall. Other rooms in the principia were used for the storage of weapons and further as offices, meeting rooms and record storage rooms. And, foremost, in the fortress the principia was the place where statues of the gods and the ruling emperors were erected.

Measuring 92.7 by 64.2 meters, the headquarters of the Nijmegen legionary fortress covered an area of nearly 6000m2. Many of the remains of this enormous building were uncovered during excavations carried out between 1918 and 1920 and between 1965 and 1967. However, due to the contemporary buildings present on the site, the remains could never be fully investigated.

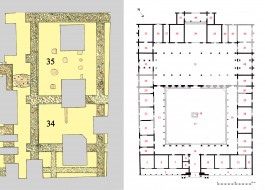

Left: map of the archaeologically examined parts of the legionary fortress in Nijmegen (yellow: headquarters). Based on: J.K. Haalebos et al., Castra und canabae, Nijmegen 1995, appendix I, E.

Right: floor plan of the headquarters, as reconstructed by Kees Peterse (black: excavated parts).

Reconstruction

On commission by Museum Het Valkhof in Nijmegen, in 2000/2001 Kees Peterse made a reconstruction of the principia, which the museum has displayed as a scale model and a series of still renderings (2D reconstructions) and a 3D animation.

Analysis of the floor plan showed that many of the measurements in metres could be converted to whole Roman feet based on a Roman foot being equivalent to 29.72cm. For example, the courtyard (17) measures 130 by 156 feet (ratio 5:6) and the wings at the sides of the courtyard and at the front along the main street are 30 and 40 feet wide, respectively. The wing with the great hall or basilica (31) and the rooms behind it is 120 feet wide. In the reconstruction of the upstanding structures, the heights were therefore also calculated as multiples of the Roman foot.

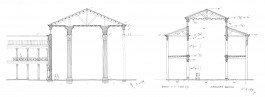

Preliminary design sketches of the reconstruction of the headquarters. Drawings by Kees Peterse.

Left: excavation plan of the south-east corner of the headquarters, showing rooms 34 and 35 (grey: not excavated).

Right: reconstructed floor plan of the headquarters with numbering of all rooms and spaces. Drawing by Kees Peterse.

The shape that the roof of the various parts of the building must have had determines the reconstruction of the upstanding elements. Rainwater had to be drained outside or into the courtyard as quickly as possible. The U-shaped colonnade around the courtyard (14-16) was certain to have had an inward-sloping roof, while the roof above the adjacent wings will have sloped outward to drain rainwater outside. The nave of the basilica (31) must also have had a pitched roof with a monopitch roof on either side above the two side aisles. An unimpeded drainage of rainwater is only possible if the basilica, including the side aisles, protrudes above the adjacent parts of the building.

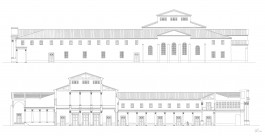

Apart from the basilica (31), four rooms in the floor plan have a special shape. On the longitudinal axis of the building, these are the entrance gate (1 and 2) and the regimental shrine (39 and 40), as well as the two rooms adjacent to the short sides of the basilica (33 and 48). These spaces must also be architecturally accentuated in the upstanding structure. In the reconstruction, the three rooms adjacent to the basilica were given a pitched roof, the ridge line of which is each time perpendicular to the outside wall of the basilica. Seen from the outside, these spaces stand out thanks to the walls being crowned with a triangular pediment with tympanum. A pitched roof has also been reconstructed above the entrance (2) at the front of the building, the gable of which is covered by the superstructure of the grand entrance (1).

Reconstructed view of the headquarters from the north. Still rendering by Gerard Jonker.

Reconstructed exterior view of the north side of the headquarters with the grand entrance. Still rendering by Gerard Jonker.

Reconstructed exterior view of the basilica (31) from the inner court (17). Still rendering: Gerard Jonker.

With the exception of the side of the basilica, the inner court (17) was enclosed by colonnades (14-16). The wall of the basilica facing the inner court had an exceptionally wide foundation, from which it can be deduced that engaged columns were embedded in this wall to continue the rhythm of the colonnades on the other three sides. In this way, too, the grandeur of the entrance to the headquarters was duplicated on this wall through this use of these embedded columns. This imposing design emphasised the significance of the building as a whole when seen from outside and the importance of the basilica and the regimental shrine when viewed from the inner court.

A large foundation (18) was uncovered at the centre of the inner court, likely the base on which a statue of the emperor stood. Seen from the entrance (2), the wall of the basilica with its engaged columns made a fitting background.

The basilica was a wide, rectangular, more or less well-defined type of building in the Roman world. It was a large, elongated hall with a broad and high nave and narrower lower aisles on either side. In the upper part of the nave, the clerestory, daylight entered through windows in the walls. The clerestory could rest on huge full-height columns, sometimes up to 50 Roman feet (almost 15 meters) high. From the floor plan and the foundations of the Nijmegen basilica, it can be deduced that in this basilica a different solution was chosen. Here, there were two rows of ‘stacked’ columns, with the upper columns being generally slightly shorter than the bottom ones.

Reconstruction of the west facade (above) and longitudinal cross section seen from the east (below). Drawings by Kees Peterse.

.

Sketch for the reconstruction of the cross section of the basilica (31), with full height columns (left) and stacked columns (right). Drawings by Kees Peterse.

Reconstructed interior view of the basilica (31) from the east. Still rendering by Gerard Jonker.

Using the measurement system incorporated in the floor plan, in the reconstruction the total height of the basilica, from the floor to the ridge of the roof, has been set at 72 Roman feet (21.40 meters), divided over three sections, i.e. 24 feet for the lower colonnade; 24 feet for the upper colonnade (shorter row of columns erected on a base); and another 24 feet for the clerestory and the roof structure combined.

The regimental shrine (39 and 40) was the main ceremonial space of the headquarters. This is where the legion’s emblems and standard were displayed, as well as the standards of the various cohorts and smaller military units that made up the legion. The adjacent rooms (here 41 and 42) were used to store the pay chests. From the foundation remains it can be deduced that the back of the regimental shrine (40) was raised; presumably, this area was reserved for displaying the emblems and standards of the legion’s military units. Buttresses were erected against the outer walls of the rooms along the back (40-42); these must have served to absorb the lateral forces of a vaulted ceiling covering these spaces.

Buttresses against the walls of the headquarters, at the level of the wing with the basilica, imply that the spaces behind these walls were also vaulted. This form of refinement in the interior is certainly in keeping with the two spaces adjacent to the short sides of the basilica (33 and 48).

Reconstructed interior view of regimental shrine (39 and 40). Still rendering by Gerard Jonker.

To learn more

A. Koster, K. Peterse & L. Swinkels 2002, Romeins Nijmegen boven het maaiveld. Reconstructies van verdwenen architectuur, Nijmegen, 20-39. [PDF]

K. Peterse, Romeinse architectuur, in: W. Willems e.a. (red.), Nijmegen. Geschiedenis van de oudste stad van Nederland, 1, Prehistorie en oudheid, Wormer 2005, 258-270 (here: 262-267).

K. Peterse, Roman architecture, in: W.J.H. Willems & H. van Enckevort (eds.), Ulpia Noviomagus. The Batavian capital at the imperial frontier, Portsmouth, Rhode Island 2009 (Journal of Roman Archaeology, Supplementary Series 73), 172-178 (here: 174-176).

Click here to return to reconstructions of masonry structures